Ireland and the Holocaust

Beginnings

From 1933 when the German Legation in Dublin dismissed their Jewish secretary Mrs Simon, the Jewish community in Ireland knew of the impending dangers of Nazi power. The Irish government was aware of the raging antisemitism but like so many other countries, closed its doors to desperate refugees fleeing Nazi Europe. Appeals were made as early as 1933 by former Chief Rabbi Herzog and Robert Briscoe to the Taoiseach Éamon De Valera and the Chief Justice to grant entry to individuals but permission was denied.

A few refugees arrived in Ireland in the years prior to the beginning of WWII, often setting up much needed factories such as Les Modes Modernes hat factory in Castlebar and the Hirsch ribbon factory in Longford.

The Emergency

The period of the war years was referred to as “The Emergency” and Ireland remained neutral. Despite this, bombs landed sporadically in the Republic, the worst event killing 34 people in North Strand on 30th May 1941. Many believed this was in retaliation for the help that was sent from Dublin to Belfast following the heavy bombing it had endured with the loss of over 800 people. An earlier bombing had taken place in January close to the neighbourhood of the Jewish Community in Dublin and damaged Greenville Hall Synagogue. This was reportedly the only synagogue for which the German government had to pay reparations.

During WWII

Ireland was isolated but news filtered in despite censorship and restrictions. There were many shortages and rationing was introduced. Military intelligence kept a close eye on potential spies, and some German activity. An internment camp was set up in the Curragh for both British and German military persons who ended up here. Despite pleas from the Allies, Éamon de Valera was firm in his stance for Ireland to remain neutral.

Many Irish Jews enlisted in the Irish auxiliary forces, the Local Defence Force and the Local Security Force as well as the British Armed Forces. It is estimated that some 130,000 Irishmen fought in the British services and over 7,500 Irishmen died in the British forces during World War II.

Murdered

Ettie Steinberg

A number of Irish citizens who had previously left Ireland to live in continental Europe were murdered in the Holocaust. Many Irish Jewish families had close relatives and friends who were killed. Ettie Steinberg whose family had come from Czechoslovakia, had attended the local national school on Donore Avenue. She married Vogtjeck Gluck from Antwerp in Greenville Hall Synagogue. They went to live in Belgium and later moved to France where their son Leon was born. All three were rounded up by the Gestapo and murdered in Auschwitz.

Listen to Ettie’s story here:

- Ettie's Story 00:00

Millisle Farm

Just before the outbreak of WWII, a group of German, Austrian and Czech Jewish children brought over on the Kindertransports found a safe haven on a farm on the Ards Peninsula in Co Down, called Millisle Farm. Previously used for bleaching flax, this derelict seventy acre farm became an unlikely sanctuary for some three hundred young refugees who, with the help of older pioneers and aid from the Belfast and Dublin communities, a Northern Irish Joint Council of Churches and the British Refugee Movement, set up a successful co-operative farm run on kibbutz lines.

After the war, a group of child concentration camp survivors were brought to Millisle farm which was eventually closed in 1948.

The true story of how these young, uprooted refugees managed to make a productive life in Northern Ireland and later, further afield, is told in Faraway Home, (O’Brien Press 1999), an award-winning book for young people by Dublin author Marilyn Taylor.

Some Irish Heroes

Hubert Butler

The scholar and writer Hubert Butler from Kilkenny was outraged at the Irish government’s attitude to Jewish refugees. Having attended the Evian Conference in 1938 and realising the plight of Jews, he worked ceaselessly with The Religious Society of Friends in Vienna processing papers for Jews and others desperate to obtain exit permits.

During Butler’s time at the Quaker International Centre, he and his colleagues helped 2,408 Jews leave Austria for various countries. Author of The Children of Drancy (1988) inspired by the transit camp from where thousands of French Jews were transported to Auschwitz, he went on to be an advocate for others who experienced injustice and he was a champion of humanitarian causes.

Mary Elmes

Mary Elmes was a Cork woman and a graduate of Trinity College Dublin who worked with the Quakers during the Spanish Civil War setting up and running hospitals under dreadful conditions. She used her skills when she crossed the border into France and worked as head of the Quaker delegation in Perpignan saving hundreds of Jewish children bound for Auschwitz from Rivesaltes Camp. She is known to have “spirited away” children in the boot of her car to children’s homes she had set up in the Pyrenees.

In 1943 she was arrested by the Gestapo and spent six months in jail, yet she continued her mission to save children’s lives upon her release. She refused all suggestion of accolades in her lifetime but in 2013 she was named “Righteous Among the Nations” at Yad Vashem. She is the only Irish person to hold this distinction, which is one given to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during World War II. On 9 July 2019 Cork City Council opened a new pedestrian bridge named in honour of Mary Elmes. Her story has been written by Clodagh Finn in A Time To Risk All.

Dr Bob Collis

Bob Collis, a paediatrician at Dublin’s Rotunda Hospital, joined the British Red Cross and St John’s Ambulance and along with a group of doctors volunteered to help at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp after it had been liberated by British troops in April 1945. There they found more than 50,000 people barely alive under appalling conditions.

He met Han Hogerzeil, a Dutch lawyer who worked alongside him to save some of the children who were dying from typhus, malnutrition, and TB. They set up a children’s hospital at the camp. After many of the children had improved in health and had been repatriated to their various countries, Sweden invited hundreds of the remaining Belsen orphans to Malmo for further recuperation.

Bob and Han then brought six of the children in his special care back with them to Ireland, where they first stayed at Fairy Hill – a hospital on the Hill of Howth. Among the children were Zoltan Zinn and his sister Edit, who had been taken from their home in rural Slovakia to Ravensbrück where their father had been murdered, and then to Belsen. Their mother died on the day of liberation and their brother shortly afterwards. Collis decided that Zoltan and Edit would live with him, his wife and their two sons.

Bob arranged the first formal adoptions in Ireland for the other four orphans, Terry and his sister Suzi Molnar from Hungary, Evelyn Schwartz and Franz Berlin from Germany. Bob and Han later married and devoted their lives to the care of children in precarious circumstances around the world.

The Weingreens

Jack and Bertha Weingreen were members of the Dublin Jewish community active in education and youth movements. Jack was Professor of Hebrew at Trinity College and both served as British Army Lieutenant-Colonels with the Jewish Relief Unit following the end of WWII.

Bertha was Chief Welfare Officer responsible for all Jewish Displaced Persons in the British zone and stationed at the former military barracks at the Bergen Belsen concentration camp.

Jack was Director of Education for all Displaced Persons and set up a successful Trade School at Belsen which was later transformed into a top-grade technical college.

They received desperately needed supplies sent from Dublin’s JYRO (Jewish Youth Relief Organisation) and the Linen Mills in Northern Ireland for the kindergarten Bertha set up for hidden children she encountered in Berlin. The Weingreens returned to Dublin in 1947 where they played prominent roles in the Irish Jewish community.

Clonyn Castle

In 1946, Rabbi Dr Solomon Schonfeld, from the Chief Rabbi’s Religious Emergency Council in London, arranged to have the 100-acre Clonyn Castle in Delvin, Co Westmeath available as a children’s hostel. The Council asked the Irish Department of Justice to admit 100 Jewish orphans who had survived the concentration camps. This was on the understanding that the Council would undertake to arrange for the children’s emigration after a specified period.

The scheme was not approved by Justice Minister Gerry Boland, and a Department memorandum noted that the Minister feared “any substantial increase in our Jewish population might give rise to an anti-Semitic problem”.

However, following a visit from former Chief Rabbi Isaac Herzog to his friend the Taoiseach Éamon de Valera, this decision was overruled, and the children were allowed in on condition that there was a guarantee that their stay would be for a short period only. This was in contrast to the admission of 500 Christian children from Germany who were admitted for three years under the Operation Shamrock scheme managed by the Irish Red Cross.

Eventually in May 1948, over 100 children arrived from Czechoslovakia and stayed in Clonyn Castle for one year where they received care and education from a network of supporters led by Mrs Olga Eppel from the Dublin Jewish community. When they left the country as agreed, they were settled in the US, Israel and the UK. Some of the children returned to Delvin for a reunion in 2000 and again in 2013 where they were warmly welcomed by the local townspeople.

Survivors

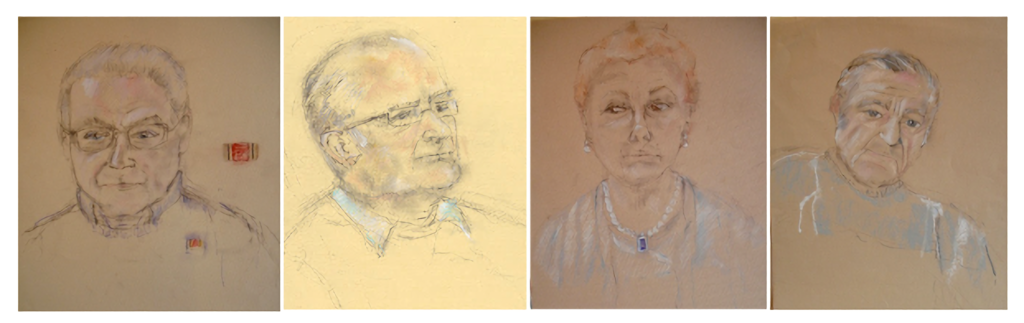

Following the war, a small number of survivors moved to Ireland. Some shared their remarkable stories of loss and suffering in an IJM exhibition based on artist Diana Muller’s interviews and portraits shown below. The last living survivors in Ireland, Suzi Diamond and Tomi Reichental are known for their meetings with students to speak about their experiences as children in the Holocaust and for their work to raise awareness of the Holocaust. Along with other refugees who arrived at the beginning of the war, the survivors led full lives and were instrumental in developing many aspects of Irish and Jewish communal life.

The Holocaust Remembered

Each year, Holocaust Education Trust Ireland organises a National Holocaust Memorial Day commemoration with the support of the Irish government. At the first commemoration ceremony in 2003, the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Michael Mc Dowell TD formally acknowledged the State and society’s failings “Whether by tolerating social discrimination, or by failing to offer refuge to those who sought it, or by failing to confront those who openly or covertly offered justification for the prejudice and race-hatred which led to the Shoah.”

The Holocaust is reflected today in Irish literature, music and the arts. As a subject, it is addressed in the secondary school curriculum.

The Irish Jewish Museum has a number of artefacts relating to the Holocaust and World War II. Most of these, if not all, were donated by individuals who had in some cases been directly affected by the Nazi regime in Europe.

INTERNATIONAL HOLOCAUST REMEMBERANCE ALLIANCE

In December 2011, Ireland became a full member of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. As a member of the IRHA, Ireland is committed to the Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust (2000) and the implementation of national policies and programmes in support of Holocaust education, remembrance and research.

Ireland’s work to implement the Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust is undertaken by a broad range of stakeholders including the Department of Justice and Equality, the Department of Education and Skills, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade along with civil society organisations including Holocaust Education Trust Ireland, the Irish Jewish Museum and academia. The museum is proud to be represented on the Museum and Memorial Committee as well as the Committee on Antisemitism and Holocaust Denial in IHRA.